Rate Books are rare survivors, since Archivists tend only to keep odd years because of the physical bulk and repetitive nature of the contents. But they can be a rich source of information, particularly in rural areas, where house numbers seldom existed and the addresses themselves were often only in the mind of the postman.

Sherborne is fortunate to have quite a number of surviving Rate Books, which list the ratepayer living in each house in every street in Sherborne. Some are held in Sherborne Museum, others in the Dorset History Centre.

The Somerset & Dorset Family History Society (the Society) is often asked for help in locating where people lived in the past, and has joined with Sherborne Museum in a project to transcribe the content of the Sherborne Rate Books held by the Museum, and to make this available to researchers.

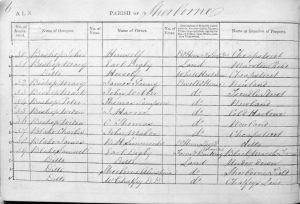

First, the actual Rate Books were photographed. Then the Society transcribes the relevant parts of the content (i.e. assessment number, occupiers, landlords, property type and street/road) to create a searchable database. Copies are held at the Society’s Family History Centre in Yeovil and in the Sherborne Museum, so that a rapid response can be given to future enquiries.

A rate is a levy for local purposes based on an assessment of the yearly value of property. The earliest rate assessments were written into churchwardens and overseers account books. They usually list the householder’s name and the amount payable for his property.

From about 1840, printed books were used, and these usually list the houses, street by street, the value of the property, the householder’s name and the amount assessed. A run of Rate Books can be very useful for researching house history. They can also be useful for family history to give an idea of when someone lived in a parish, or when family property changed hands.

Survival of Rate Books depends upon circumstance and chance. Many have been lost, as population growth (especially in urban areas) led to a huge increase in the number of rate books produced, and many authorities simply destroyed the records rather than find somewhere to store them.