Remembering Bertie and Reg

Posted on 11th November 2018

Foster’s School Sherborne 1910. Bertie Brooks far right and Reg Palmer back row fifth from left. Photo held by Sherborne Museum

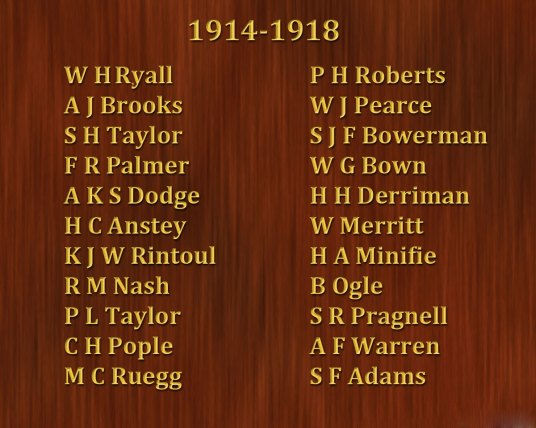

I would like to tell you about two boys who died in World War One. They had both attended Foster’s School, in Sherborne, and you can see their names on the Roll of Honour board (now at the Gryphon School.)

These two boys became firm friends and would have had no idea that their carefree schoolboy games and exercises would be followed by such an abrupt end to both their young lives.

The first boy is Francis Reginald Palmer, or Reg as he was known. In 1907 at the age of 13, an age at which many boys ended their elementary education and headed out to work, Reg was awarded a Governors’ scholarship to Foster’s School and so began his secondary education. He was a bright and talented boy, whose party piece was playing the piano with a glass of water balanced on the back of each hand. He was the only child of Arthur and Annie Palmer. Arthur Palmer was the caretaker at Sherborne Girls’ School.

Around the same time, Thomas Hutchins took up the post of headmaster of Foster’s School and within a short time he started the school magazine The Fosterian and it is from copies of this magazine that much of this information about Reg and his friend Bertie Brooks has been extracted.

Albert John Brooks joined the school from Beaminster Grammar School in September 1908. Bertie was the eighth of nine children of George and Mary Brooks. George was a Superintendent of police with Dorset Constabulary and had retired to Trent and Bertie transferred schools with a scholarship from Dorset County Council. I have a personal interest in Bertie as he was my first cousin twice removed.

Christmas 1908 and Bertie and Reg appear together in the school production of The Merchant of Venice and I think it most likely that during the rehearsals the friendship between the two boys began. The following summer they took part in the school sports team, travelling to Blandford for the inter-schools sports day. Another member of that long ago team was Percy Taylor, and if you look at the roll of honour board you will see his name there as well. Percy’s older brother Sidney is also remembered on the board.

In 1911 the headmaster reported that it had been a year of ‘Work, Races and Chases’. Reg and Bertie had been working hard at their studies and had both passed the Oxford School certificate examinations at senior level with eight subjects each. The chases referred to the cross country paper chases which were a popular feature, for some, of school life. Reg and Bertie are rumoured to have ‘chartered a passing motor and finished the last few hundred yards at a somewhat higher speed than the afternoon’s average.’ I think this was contributed, with tongue in cheek, by Bertie himself.

The two friends then went on to sit the Cambridge Senior examination which they passed qualifying them both to go on as student teachers. The headmaster reported that they returned to the school for teaching practice where they continued to spend Tuesdays giving everyone the benefit of their ideas, both scientific and literary.

The last mention by the headmaster of the two boys at this time appears at Easter 1913:

We are glad to record that Brooks and Palmer, who have been with us for many years past, and who continued to attend School last year as Student Teachers, the teaching part of their time being spent at the Abbey School, have now been appointed provisional Masters near London. They will enter into residence at Training Colleges next October. They carry with them the best wishes of all the Masters and of all the boys.

The following year on 4 August 1914 war on Germany was declared and the headmaster reported in The Fosterian:

‘How wonderfully do circumstances change the value of things! As I write here about our games, our sports and even about our work of last term our countryman in France are meeting death, wounds, hunger and fatigue like heroes.’ He continued ‘A J Brooks went through Sherborne looking very pleased at the prospect of joining the Grenadier Guards for which he had been accepted.’

Summer 1915 and there is mention of Reg:

‘Congratulations to 2nd Lieutenant F R Palmer who has joined the Dorsetshire Regiment and has just completed a month’s training in Oxford.’

Since we last heard of Reg he had moved on to take up a place at Bristol University and he had enlisted from there. He most likely would automatically go into the officer corps as he was entering from a University. The month’s training at Oxford may have included instruction in the art of being a ‘gentlemen’ which it was assumed would bring with it the associated leadership skills. It is perhaps worth noting here that to be a young Lieutenant was probably one of the most dangerous of all first world war occupations as it was their job to lead their men from the front. They would be targeted by German snipers in order to create the most havoc and confusion.

In the Christmas 1915 edition of The Fosterian the headmaster has the difficult task of reporting the first death from amongst the seventy or so old boys who have joined up by this time and it is my cousin Bertie:

He said: ‘A J Brooks, whom but a short time ago we saw leaving Sherborne to enlist in the Guards, has been missing since September. He was with the Grenadiers at Loos and when, after an attack, they had to retire it is feared he fell and was left upon the field. Brooks was a fine lad, who had equipped himself for fighting life’s battle and would assuredly have earned the success in life he merited had not his country and his duty called him’. Bertie had been killed at the battle of Loos on 27 September 1915 and, despite the headmaster’s fine words, the family back home in Trent would have been completely devastated as Bertie was the second son to die in this war. Two other sons of George and Mary had left for Australia and a new life several years previously. From there they had both joined up and had been sent to Gallipoli where William, the elder of the two, was killed on 23 July. His younger brother Percy was buried in a collapsed trench for three days, with only his boots sticking out before he was rescued. Suffering from what was said to be ‘only partial deafness’ from this experience he would be sent on to France to continue his war. Needless to say Percy never really recovered and when his only son was killed in the Second World War Percy committed suicide.

Bertie was not the first of the old boys of the school to be lost as Harry Derriman fighting with the Wellington Mounted Rifles of New Zealand was killed on the 9 August at Gallipolli and Stanley Adams, while fighting with the Dorset Yeomanry, was killed on 21 August at the Battle of Scimitar Hill also in Gallipoli.

Each edition of The Fosterian contains letters back to the school from Old Boys and in the December 1916 edition a letter has been received from Reg who writes:

‘I am not going to try and portray actual fighting or a battlefield as in the first place I do not remember much of either, and wouldn’t if I could. At 6.10am we were awakened by our servants who said late orders had come that breakfast was at 6.30 – valises to be ready for packing at 7.00 and battalion to move at 7.30. No-one knew where, but the fact remained we were to move. Shaving in cold water at 6.15 sharpens the appetite. We got to mess at 6.30 and found everything packed-up, ergo no breakfast and no rations in our haversack. At 7.30 we marched. Try and picture a road ankle deep in mud, and every few yards having to make a detour through a shell hole. All the time we are marching in imminent peril of being crushed by motor lorries or mules. At 11.10 we arrived at camp, a scene of great fighting last September, and now made into a camp by stretching waterproof sheets over shell holes. At 4.30 we proceed with a guide from the battalion we are going to relieve, and reach Brigade Headquarters. Here we find it necessary to hurry as the Boche is whizzbanging the place and proceed with the platoon guides. Personally I never saw any guides and was soon left in a sunken road with 30 men of our own company and 30 and 20 of others nearby. The guides had disappeared in the dark to find the track. Presently they returned and we proceeded over moors with no landmarks to guide one and the moors themselves one mass of holes so close together that there is only room for one man at a time to go between them. Presently the guide announces he has lost his way, and, although new to the place, we decide to carry on over nothing more than a continuous slush heap. A man thinks he has got a good foothold, uses it, and promptly goes in over the waist. We pull him out amidst much Barnsfather language. Three hours of this and we at last find a trench, slither over top, take over stores, relieve sentries. The platoon commanders shake hands and wish each other ‘Cheerio’ and the other regiment files out. We are left in a soaking trench, not revetted, not possessing a dug-out and everyone proceeds to dig a hole in which to sit. We expect a ration party at first light but a wire comes through saying they have lost their way, and returned whence they started. We have no water that night, but two adventurous spirits creep out to a shell hole and fill their water bottles with the water they find there and everyone goes mad with delight. Later on the rations arrive, bully, biscuits, jam, water and a tablespoon of rum per man. In due time we are relieved and walk into a barrage of lachrymose shells, but at length safely reach the Camp of —–Wood, where we stop till our time comes to go up the line again’.

Reg Palmer was just 24 years old and seven or eight years earlier he was running around the countryside near Sherborne leading the hounds in a paper-chase with his good friend Bertie Brooks.

A second letter was received: ‘Since writing you I have had a month in billets where we were to get beds with real sheets and pillows. Now we are up the line and shall probably spend Christmas with a firework demonstration. When we are in rest billets it generally means running drill for half an hour before breakfast, parades 9-1, with the afternoon devoted to sport and at night from 8.30 -12 is night work – with a route march of not less than 12 miles once a week. We really have an easier time in the trenches but of course we get no sleep there, and plenty of shelling which puts the wind up one’.

In the Easter edition 1917 of The Fosterian, the headmaster started straight away to announce that three former pupils had given up their lives and, written within a heavy black border, he states:

‘R F Palmer, S Taylor, and K Dodge. The first two nobly fell while leading their men and K Dodge fell during his period of training. These are but three of the thousands of lives which have been given up to ensure our safety’.

Reg died on 23 April 1917 fighting at the battle of Arras which raged for over a month near the French town.

We cannot comprehend what this news will have meant to his loving parents, who had lost their talented only son with his lively mind who had done so well at school that he had gone on to university; a quite unheard of achievement amongst their family and friends. He was also planning to instil in others the love and desire for education that he so clearly had found in himself. A complete and utter tragedy for them both to try to comprehend.

Later his mother went on to donate an honours Board in 1918 and a second one, containing additional names in 1932. She died in 1934 but before her death made provision for a History prize in memory of Reg, and a French prize in memory of his friend Bertie and in her will she left £426 to the school (later used to panel the library for the new school which opened in 1939).

I will leave the final words to the headmaster Mr Hutchins who steered the school through this most difficult of times:

“The shadow of war falls over few places more darkly than over a boys’ school. Old boys join up and depart to do their duty, Masters answer the call of the country and older boys leave to take the places of those who have gone to fight. At the outbreak of war the school numbers immediately diminished by one quarter”

The Roll of Honour now hangs at the Gryphon School, Sherborne

Barbara Elsmore 11 November 2018