Historic Migration from the West Country

Posted on 14th July 2018

I must preface this article by stating that I am no expert on migration – this post is merely a transcript of my notes on the recent seminar, held to mark the 20th anniversary of a similar event held in Lyme Regis in June 1998. I hope I have done the talks justice. The seminar was a full-day seminar and gave an excellent over-view of migration from the West Country. Examples from all West Country counties were mentioned, as were all the main destinations – America, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Liz Craig.

Historic Migration from the West Country: a study revisited 20 years on

Saturday 9 June at Loders Village Hall

“An emigrant’s last sight of home” by Richard Redgrave in 1858. It was often a last farewell as it was prohibitively expensive for migrants to contemplate returning home.

Farm, Fish, Faith or Family? Motivations for emigration from North Devon 1830 –1875 – Janet Few

As soon as I saw Janet’s name on the programme I knew we were in for a treat; for those of you who have never heard Janet speak, she is an expert on a wide range of genealogical subjects and her talks are always full of well-researched, interesting information with a dose of humour woven in. Janet emphasised that the reasons for migration are multi-faceted – potential clues as to the reason for migration may be found in the date, new location, previous location, travelling companions (i.e. part of a chain of family migrations?), occupation and religion.

Reasons for migration are usually economic, but other explanations include education – a more modern explanation – historically this may have been for apprenticeship, familial (parents’ occupations), personal choice, religious (e.g. persecution), political regimes, avoiding natural disasters, forcible removal and escaping justice. These still explain many reasons for migration today.

Between 1840-1900, 434,806 people left Britain through a Devon port. Nationally, 75% of Victorian migrants went to America, but in Devon only 1.1% went to America, most were destined for Australasia. Janet discovered several preconceptions about Devon migration:

- That they were ag labs (agricultural labourers) looking for land in the new world

- That emigrants were usually single

- That the connection with Newfoundland was due to the cod trade

Patterns of religion in North Devon were much more akin to Cornwall than they were to South Devon. Many Methodists experienced low levels of antagonism at home, even being subjected to “personal violence for conscience sake”; others went overseas to evangelise. Religious migrants tended to settle where others who shared their religion had already settled.

We often assume that migrants tend to go to big cities, as part of the industrial revolution, but Janet found that this was not the case in North Devon – they tended to move to other rural locations within a 15-mile radius, or travel abroad.

Janet then presented case studies of five families – including one in which a whole generation moved. She re-visited some of the preconceptions she outlined at the beginning of her talk. She concluded that

- Many of the migrants were already farmers, rather than ag labs

- Migrants were not usually single

- The fish trade was in decline during the period 1840-1900, so was not a factor

There then followed six 10-minute presentations from Jane’s students, giving examples of migrations from their own research:

Case Study: Cornish Coast Guard Migration within the UK – Sue Wilson

Sue’s talk on her ancestor William Mynheer, from St Mawes in Cornwall, was to illustrate occupation as a motivation for migration. She emphasised the importance of looking at the local and national context surrounding a person’s life. William’s mother died when he was a child. Britain was at war with France, there were constant fears of a French invasion. Bad winters caused poor harvests and bread was scarce. William first went to sea as a boy aged 13 in 1802.

William moved away from Cornwall, and Sue wondered how typical this was. She established that no boatman was to work within 20 miles of his home, not lodge with smugglers, and should live near to his place of work. Sue was able to track his movements using the Database of British Coastguards on Genuki. She looked at 159 of William’s contemporaries, born between 1764 and 1799. 47% had moved out of the county and never returned. 20% left the county and went back. 18% moved elsewhere in Cornwall, many to the opposite coast. 11% broke the rules of employment and stayed in their home town.

Case Study: Incomers into Cornwall, marrying local girls and moving out – Jackie Hewitt

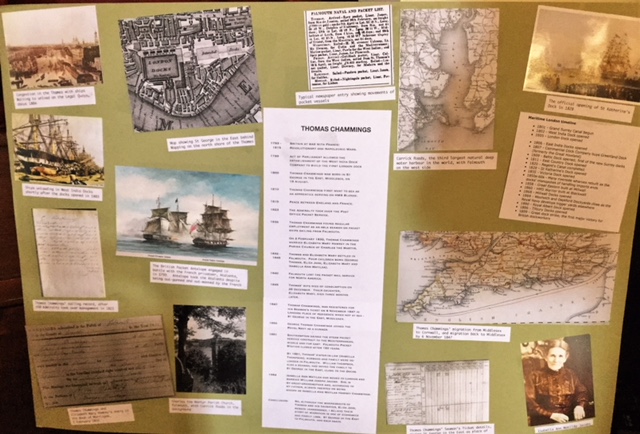

Jackie told us about her ancestor Thomas Chammings, who was born in St George in the East, London, in 1800. The previous year, the East India Company was formed. There was congestion in the River Thames, with ships queuing up to land their cargo in the 20 legal quays – it was said that you could cross from one side of The Thames to the other without getting your feet wet!

Jackie told us about her ancestor Thomas Chammings, who was born in St George in the East, London, in 1800. The previous year, the East India Company was formed. There was congestion in the River Thames, with ships queuing up to land their cargo in the 20 legal quays – it was said that you could cross from one side of The Thames to the other without getting your feet wet!

Britain had been at war with France since 1793. Britain needed ships and seamen – including pressed men. Thomas first went to sea in 1810. By 1823, the Admiralty had taken over the Post Office Packet Service, bringing post, bullion and news from the plantations back from overseas. Falmouth was the port of choice because of its deep-water anchorage, close proximity to the open sea, and because it enabled ships to dock without having to run the gauntlet of the English Channel. The main drawback was Falmouth’s distance from London.

Thomas moved to Falmouth, married, settled, and had 4 children. He served on packet ships in the 1830s. By the late 1830s, the packet service was in decline. In 1850, the contract was awarded to Liverpool. Thomas and one of his sons returned to London, knowing they could get employment in the docks.

Case Study: Three generations of one Cornish family going all the world – Wendy Hilton

Wendy told us about the Bray/Morcom family, three generations of which migrated – one to Wales and the other two to Australia. Richard Morcom went to Gwennap in Wales. He was a manganese miner but used his transferrable skills to branch out into copper mining. He then moved to Cornwall to mine, then Exmoor, and then Anglesey where he worked as a mining agent in the 1850s.

Grace Bray married William Truscott, and emigrated using the assisted passage scheme, which cost £2 per couple and £1 per child. Her husband Walter described himself as an ag lab – the passage was cheaper for unskilled workers. Their ship docked in Adelaide. Migrants could stay on the ship for two weeks while they looked for work; however, some passengers disappeared straight away and headed for the gold fields in Victoria – there were no assisted passages to Victoria, so they had taken advantage of a cheap passage and then gone to pan for gold! Grace and William then moved to Clare, a farming settlement established 10 years previously.

Grace’s nephew William Henry Bray joined the Navy in 1883 as a carpenter. He jumped ship in Sydney. Perhaps he had heard from his aunt that there were opportunities to be had in Australia. He used his carpentry skills to make furniture and settled in Goulburn, Australia’s first inland town.

Case Study: From Gloucestershire to Dorset – Ken Isaac

Ken told us of his Isaac family’s journey around England over the course of 110 years. Ken’s Isaac family worked on the Badminton Estate near Tormarton (near Bristol), then to London, then on to Windley in Derbyshire. His great grandfather was working as a dairyman and later a coalman. They later moved to Christchurch (then in Hampshire), Pokesdown (near Malvern) and then to Portland. Ken drew parallels with his own working life; he and his wife moved around the country due to Ken’s work.

Case Study: Somerset to the US: taking their skills with them – Jane for Margaret Young

Margaret was not able to attend, so Jane delivered her presentation on the Gayner family, an excellent example of an ancestor taking a trade with him. Margaret’s ancestor John Gayner was a glass worker in Nailsea. You can read more about the Nailsea glassmaking industry here and here. His wife and several of their children died. For economic reasons, he decided to emigrate to the USA. In 1866 he landed in Maine. He moved from one glass factory to another, living in New Jersey in 1880. The 1900 census enabled Margaret to calculate his emigration date of 1866. Eventually he settled in Salem and founded the Gayner Glass Factory in 1898. The 1900 census is useful to establish an emigration date if you have been unable to find your ancestors on passenger lists.

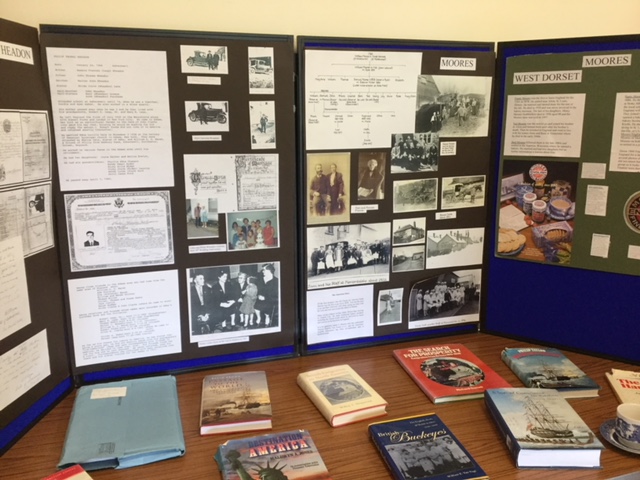

Case Study: Dorset Meatyards in America – Jane for Caroline Meatyard

Robert and Betty Meatyard emigrated to New York from Bradstock in 1835; Robert described himself as a farmer. He bought land in Illinois and by 1850 had three children. The 1851 census shows them back in Bradstock; perhaps our emigrant ancestors visited home more often than we thought? However, by 1860 Robert had returned to Illinois with two of their sons, while the 1861 census shows Betty and son James living in Chardstock. In 1869, Robert bigamously married again. Betsy accused him off bigamy in an English court and was granted a divorce. Betsy had returned to Bradstock by 1871, and the census entry is interesting because it appears that her marital status was originally given as divorced – which was then crossed out and replaced with the word ‘unmarried’.

Caroline is doing a one-name study of the Meatyard name. If you have any Meatyards in your family tree, I am sure she would love to hear from you!

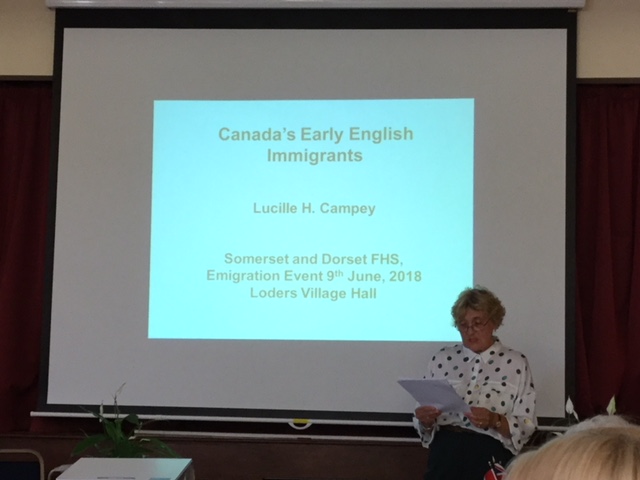

Emigration from England to Canada, examples from Dorset – Lucille Campey

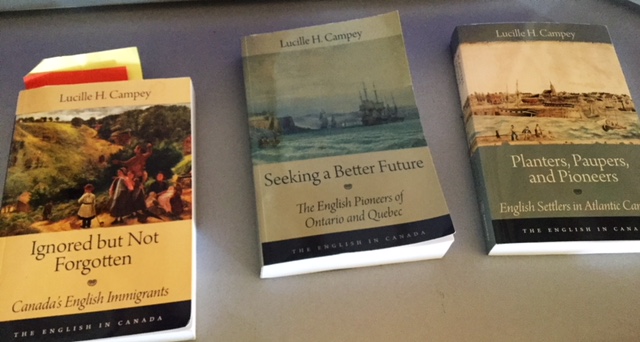

Lucille is the author of several excellent books, three of them focussing on emigration from England to Canada – Ignored but Not Forgotten: Canada’s English Immigrants, Seeking a Better Future: The English Pioneers of Ontario and Quebec, and Planters, Paupers and Pioneers: English Settlers in Atlantic Canada. Her thirteenth book, on emigration from Scotland to Canada, will be published shortly. She packed so many interesting facts into her talk that I struggled to keep up, but here goes!

The English came to Canada after the Scots and Irish, once they had seen it as the land of opportunity. The English merged quietly into Canadian life – none of the parades or flag-waving of the Scots and Irish. Coming from a great empire, they did not feel the need to explain or express themselves, and at times came across as being aloof.

Emigration from England only began in great numbers from the 1830s. Parish-funded schemes funded many assisted passages especially after the mechanisation of farming which reduced the need for agricultural labourers. In some cases, it was cheaper for the parish to pay for a pauper’s assisted passage than it was to continue paying poor relief.

Many English emigrants to Canada went to Ontario, one example being the Tolpuddle Martyrs who, having returned to England after their transportation to Australia, decided that they no longer wanted to remain in England and emigrated to London, Ontario.

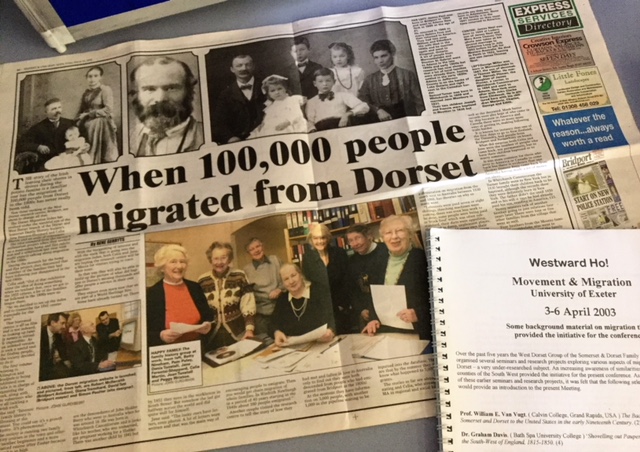

In the 1870s, many Dorset farmers emigrated to Canada. Mounting patriotic feeling swung migration from the US to Canada. Canada was frequently promoted as a land of opportunity. One man (George Dennison?) gave talks around Dorset and Wiltshire, talking in the open air and on village greens, encouraging labourers to emigrate to Canada. Farmers were justifiably worried about losing labourers – many Dorset farm workers left for Ontario as a result of this tour. As many as 100,000 migrants per year came to Canada.

Canadian produce was prominently displayed in horse-drawn wagons which were brought to agricultural shows and weekly markets. Immigration experts were on hand to distribute pamphlets and report favourably on Canada’s prospects.

Inhabitants of the Canadian Prairies were mostly English, with very few Scots and Irish. The railway often didn’t take them all the way to their destination and frequently the journey ended with families walking a great distance carrying their possessions. The transition to prairie life was daunting to some – especially those who’d had servants in England. Some women worked as domestic servants and were embarrassed to admit it. They couldn’t afford servants in Canada as wages were high and their attitude to having to do these manual tasks themselves at times made them come across as snooty. By 1911, the English were the largest ethnic group in Manitoba, especially in the south. The English took a while to realise that the Canadians didn’t care about social standing or who your father was.

In Victorian England, large families became common, and one or two members of the family were encouraged to go to Canada to contribute financially to the family’s income.

In Alberta the younger sons of wealthy English families spotted Alberta’s potential for cattle ranching. The Canadian government’s 1890s campaign encouraged migration to British Columbia. Gold and coal deposits encouraged Cornish migrants, who were engaged in similar occupations at home. The fruit-growing conditions of the Okenagan valley were also an attraction.

In addition to migrants seeking a better life, Britain deposited their destitute and unemployable citizens, which was not what Canada needed. For example, 52 boys were sent from Manchester and Salford refuges, orphanages and workhouses. These migrants were used as cheap labour and often abused, although Lucille found that they often made good lives for themselves as adults. You can read more about British Home Children in Canada here.

An assisted emigrant – means that someone at the other end had organised land for them. Often land was taken by squatters. Land speculators caused great problems.

Lucille’s recommended sources include the Library and Archives of Canada, the Saskatchewan Archives, and the Glenbow Archive, and the Remittance Books in the Ottawa Archive – remittance being when someone settled in Canada and sent money back home to enable relatives to join them.

Finding sources for researching migrants to the USA – Jane Ferentzi-Sheppard

Jane gave a short talk on sources for finding migrant ancestors, including baptisms, vestry minutes, wills, shipping lists, newspapers, Castle Garden, Ellis Island, naturalisation papers, and censuses. Some US land maps give the names of the people who lived there.

We were then treated to four more 10-minute presentations from Jane’s students, giving examples of migrations from their own research:

Case Study: Dorset Mormons in the US – Sally Beadle

Sally told us the story of her ancestor Thomas Mabey’s arduous journey from Mapperton in Dorset to Utah. Thomas married Esther Chalker; they and their children became Mormons and emigrated to Utah in 1862. The Mormon Church was founded in the 1820s in New York by Joseph Smith. Smith moved to Kirkland, Ohio, then to Jackson, Missouri, from where he fled in 1833 following violence and threats from locals. Smith died in 1844 and his successor Brigham Young led the members of the Mormon Church (renamed The Jesus Christ Church of Latter Day Saints) to Utah.

Thomas and Esther’s daughter married and converted to Mormonisn, and the rest of the family converted soon after. I was surprised to learn from Sally, that there were quite a few Mormons in Dorset at this time. It was considered a Mormon’s duty to emigrate to Utah. It took Thomas Mabey two years of hard work to raise the funds to emigrate. The family sailed in 1862 with 376 ‘saints’ (as the Mormons referred to themselves) and after a 5-week journey, they arrived in New York.

5000 settlers arrived in Salt Lake in 1862. There were two classes of converts – those who could pay their own way and those who could not. It was an arduous journey, by wagon train, and involved walking 15 miles a day. Only the elderly, infirm and children could ride. At night, they would park the wagons in a circle to form a camp.

It took 5 months to get to Utah from Liverpool. They were taken in by families, who housed and fed them until they were able to set up their own homes. Roads, bridges, homes, and meeting rooms were built. Land was cultivated and the soil was fertile. They grew mulberry shoots and bought silkworms. A range of crops were grown, and animals were kept.

Sadly, Thomas died 5 months later. He and his family worked hard and paid back their debt to the church. His surviving family were part of a strong church and social life. Esther and her family moved several times, improving their situation each time.

Sally is fortunate that her ancestor’s son Charles Randall Mabey wrote a memoir, and if his book (republished in 2016) is anything as good as Sally’s talk, then it will be a very good read indeed!

Case Study: Devon, Dorset Channel Island links in the 1840s – Paul Radford

If Paul’s name sounds familiar, it’s because he is the editor of our esteemed journal, The Greenwood Tree. Paul told us how he discovered that three of his ancestors who lived within 30 miles of each other all migrated to Guernsey within a decade of each other. He was intrigued by why they had chosen Guernsey and decided to investigate further.

He discovered that Guernsey had a thriving economy, offering potential employment in granite quarrying and ship-building. Road-builder John McAdam preferred Aberdeen and Guernsey granite for road-building. In 1847 there was a restriction in 1847 which said that no granite which had been cracked within 20 miles of London could be used in road-building.

Also, Guernsey was easily accessible – you could get there in a day. St Peter Port became prosperous in the 18th century mainly due to privateering and smuggling. The population doubled between 1821-1911. The highest number of migrants was in the 1840s. 22% were from Devon, 14.6% from Cornwall, 14.5% from Dorset, and 14.2% from Somerset. Some returned to their home county, but others stayed – Paul recommended that if there’s a gap in our ancestors’ lives, it is definitely worth checking to see if they spent time in the Channel Islands.

Paul reminded us of a previously published excellent resource – a special supplement in The Greenwood Tree. If you missed it, why not view it on the ’40 Years of the Greenwood Tree’ available on either CD or memory stick, available from our online shop.

Case Study: Assisted Passages to Australia – Sue Thornton-Grimes

Sue’s husband Laurence did an MSc with the University of Strathclyde and became interested in emigration. He needed a manageable-sized project to research, and decided to investigate the period 1830-1860; why did agricultural labourers leave during this period? How did they leave?

Agricultural Swing riots and mechanisation had an adverse impact on the lives of ag labs during this period. Australia was being opened up. Government schemes offering assisted passages were available in 1831. One such scheme was the McArthur bounty scheme. The McArthur brothers of Camden, New South Wales, wrote to John West, the rector of Chettle, wanting people to work on his estate. John West vouched for several families, enabling 236 people to emigrate. McArthur organised school and church. You can read more here. A similar scheme was facilitated by the Reverend Lord Sydney Godolphin Osborne, who sent a large group of emigrants to Australia.

Laurence decided to collect as many names of migrants as possible, collecting information about what type of people were leaving Dorset, their occupations, etc. He used lots of sources, such as emigration lists, certificates of departure and passenger diaries. He made good use of online sources such as the Australian Immigrants 1828 – 1896 database on Ancestry, which is a combination of four databases. He used ‘Dorset’ as a keyword in the origin box.

Laurence created a database with 16 fields, including age, gender, status, whether they could read/write, and whether they had a sponsor or not. This data extraction provided 1170 records for analysis. Just over half were make. 477 were aged 0-13. Only 14 people were aged 50-66. 46 were sponsored by the McArthur brothers. Between 1849-58, 157 more people emigrated, having been sponsored by people who were already there. Ag labs were the most frequent occupation – 259 of them sought a new life in Australia, as did 123 (farm & indoor) servants; 1 schoolmaster; 29 dressmakers, button makers and glovers; and 20 shepherds.

Sue and Laurence hope that the database will enable those who haven’t been able to find their emigrant ancestors to locate them. Their work also enables us to see a richer picture of those leaving Dorset for Australia in that timeframe, and their motivations for doing so.

Case Study: Sartin Family: Corscombe to New Zealand – Bonny Sartin

Bonny Sartin talked to us about his ancestors Lucy and Edmund Sarten of Corscombe, Dorset, who in 1840 set sail on the ship William Bryan from Plymouth, arriving in New Zealand four months later. Bonny has been able to supplement his knowledge of their journey thanks to the diary of the ship’s doctor, Dr Henry Weekes, which describes uncomfortable levels of dysentery and malnutrition. The journey wasn’t all bad though; there were parties on a Saturday night, which included a ‘sing-a-round’ – a new song had to be sung every week. There were occasional dances, accompanied by the fiddle, flute and copper kettle!

The ship sailed to what is now known as ‘New Plymouth’. The Maoris had planted extra crops to feed the new settlers. The Maoris later realised that they had been conned out of their land and this lead to the 1st Maori War, in which two of the Sarten boys were killed. Another son went to the gold mines in the South Island. Another son, Levi ‘Hole in the Wall’ Sarten, was a successful farmer with an interest in local politics. He became a councillor and oversaw the building of two bridges. He earned his ‘Hole in the Wall’ nickname due to a scheme he devised to deal with the problem sand drifting into the harbour – he suggested that a hole in the breakwater would remedy the problem, but the scheme was never carried out.

Bonny ended his talk with a rendition of one of the traditional songs that his ancestor sang. It was the perfect way to end a fascinating and informative day!

The day ended with a plenary discussion with speakers and guests. Jane is hopeful that a special interest group focusing on migration studies might be formed to build further upon what has already been achieved.

Liz Jones – July 2018